The History of Usa Jingū (Part 1 – The Ancient Times)

Usa Jingū (pronounced U-sa and not U.S.A) is an ancient and influential shrine in Japanese history; yet surprisingly has remained hidden under many tourist’s radar. Reason being its secluded location in north-east of the island of Kyushu (九州) which is mainly a rural area with a few smaller cities. This area is known as the Kunisaki Peninsula (国東半島) and is famous for its rural areas, mountains and agriculture. Despite this, Usa Jingū is one of Japan’s major shrines and has a rich and colourful history behind its origin. To fully appreciate its significance, lets deep dive into its background.

Table of Contents

How It All Began

Birth of Usa Jingū in Ancient History

Usa Jingū was first founded in the 8th century Japan in the Nara period (Nara jidai/奈良時代), an ancient historical period that lasted from AD 710 to AD 794 but was crucial in Japanese history for a few reasons. It was when Japan finally established their official capital in Nara (奈良) after shifting capitals for many centuries. This symbolises the fact that Japan transformed from a nomadic lifestyle to a full-fledge government.

Buddhism (Bukkyō/仏教) also entered Japan in this period as a new religion and became an overnight pop-culture sensation. In AD 725 the Shinto priests and Buddhist monks collaborated to built Usa Jingū, displaying the cooperation between Shintoism (神道) and Buddhism (Bukkyō/仏教). These two religions were of completely different background and butt heads with each other; hence why the sudden collaboration between the two?

For the Shinto side, while they have a stronger dominance in Japan, they were lacking in writing and architecture skills. In contrast, the Buddhists had prior experience in those from India and China but wanted to expand their influence further. What better chance for both sides to collab into a project and fuse their religions. Little did they know their mini project would pioneer a whole new culture in the country.

How Usa Jingū Pioneered A Culture in Ancient History

The Birth of Hachiman

If there is a culture this shrine has pioneered, it was the worship of Hachiman (八幡) in both religions; the first multiverse deity in Japanese history. Originally a local god worshipped by farmers and fishermen to pray for good harvest and catch, he became the god of worship in Usa Jingū. Eventually, the Shinto priests promoted him to the God of War and Archery, transforming him as the protector for the people and elevating the status of the shrine.

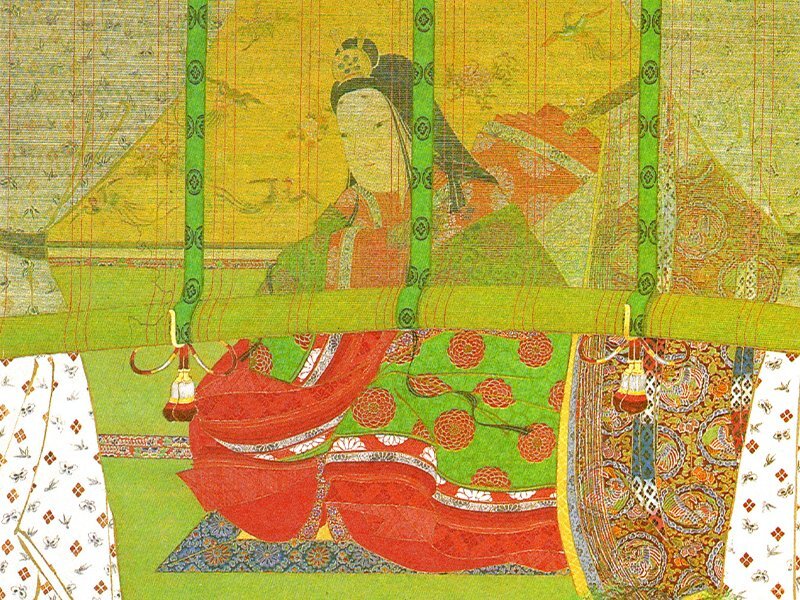

The Buddhists promoted him to a Bodhisattva and bestowed him as Hachiman Daibosatsu (八幡大菩薩), meaning Great Hachiman Bodhisattva. They relocated him in AD 747 to the prestigious Tōdaiji temple (東大寺) in Nara (奈良) by using an elaborately decorated palanquin (mikoshi or omikoshi to be more respectful/神輿). This was a luxury equivalent to travelling on a private jet.

Later during the aristocratic Heian period (Heian Jidai/平安時代) from AD 794 onwards, the Imperial Court declared Hachiman (八幡) as a deified spirit of the legendary Emperor Ojin (応神天皇). A master in foreign affairs; Emperor Ojin invited foreign scholars into the land and promoted their ideology, making him the suitable candidate in this case. This political move to deified him served to establish the influence of the Imperial Court among the people; as whoever controls religion controls the people.

Hachiman’s Identity Evolves Further

Eventually, the samurai warrior class Minamoto clan (源) adopted him as their patron deity as they were descendants of Emperor Ojin. The Minamoto were experts in horsemanship and archery; and decided his shintai (身体) or worship object to be either a bow or a stirrup. The Minamotos would eventually engaged in a major civil war and transformed the tides of history of the country. Ironically, they were also responsible for burning Usa Jingū. More about this incident in part 2.

Over the years, Hachiman’s identity transformed from local to a national deity; mainly contributed by the influence of court officials, religious factions and samurai (侍) warriors. These were the dynamic trio in the politics of the country and their actions largely influenced the beliefs of the commoners. Shrines worshipping Hachiman sprouted like new Starbucks outlets across the land and became a popular cult.

Usa Jingū and the History of the Rokugo Manzan Shrines and Temples

What is Rokugo Manzan?

First of all, what does this mumbo jumbo means? Rokugo Manzan (六郷満山) literally means ‘six towns full mountains’ refers to the group of temples and shrines that are within the Kunisaki Peninsula (国東半島). Traditionally, this peninsula filled with spectacular mountains comprised of formerly six areas; hence its literal name. For the Japanese history geeks, the six areas were Kunawa (来縄), Tashibu (田染), Aki (安岐), Musashi (武蔵), Kunisaki (国東) and Imi (伊美).

Legend has it that a monk named Ninmon (仁聞) from Usa Jingū discovered this scenic landscape and developed numerous temples and shrines in the early 8th century. Remember that Usa Jingū is both a Buddhist temple and a Shinto shrine, and its elements were incorporated into the new temples and shrines. Additionally, they incorporated other religions from mountain worship and Taoism which transformed into a hybrid worship culture.

Rokugo Manzan’s Impact to the Society

The hybrid mix of Shintoism and Buddhism sprouted many shrine-temples (Jingū-ji/神宮寺) throughout the country. So much so that locals created a term based on it in the 17th century, known as Shinbutsu shūgō (神仏習合). Shinbutsu (神仏) means both Shintoism and Buddhism while shūgō (習合) means to combine/assimilate. This practice significantly impacted the lifes of the locals, such as rituals, prayers and funerals. Unfortunately, a certain over-nationalistic government threatened this practice in the 19th century and almost caused the destruction of the shrine. More on this in part 2.

Usa Jingū pioneered the unique shrine-temples (Jingū-ji/神宮寺) and the worship and building of Hachiman shrines. With such accomplishments, you did think that things would go all that smoothly and wonderful for the shrine, right? Wrong, as Usa Jingū experienced various political drama and civil wars throughout its history; including a scandalous relationship between a monk and an empress.

Usa Jingū Endorsed a Monk to be an Emperor First Time in History

When A Monk Dates An Empress

Did you know that a monk was going to rule Japan at one point of time? Back in the Nara period (奈良時代), a Buddhist monk named Dōkyō (道鏡) dated an empress and almost became emperor himself. The ruler at that time was Empress Kōken (孝謙天皇), one of the only eight exclusive female rulers in Japan.

Empress Kōken (孝謙天皇) also lead a chaotic life of political coups and was once forced to abdicate in favour of a younger cousin. Yet fortune smiled upon her when a Buddhist monk named Dōkyō (道鏡) cured her when she was ill (Dōkyō was around his 60s while the Empress was around her 40s during this time). Both shared a common interest in Buddhism, and they started dating. Under the monk’s guidance, she developed a new interest in Buddhism and started printing and distributing sutras throughout the country.

Despite her age, she was a hyperactive person herself and ruling behind curtains was not a means to an end. With some extreme political maneuvering, she exiled the Emperor; and ascended the throne once again as Empress Shōtoku (称徳天皇). For the remainder of this article, we will still address her as Empress Kōken. Dōkyō was the one who supported her during her supposed ‘retirement’ and he immediately became her favourite subject.

The Empress showered him with fortunes and titles, one of them being the Daijō-daijin (太政大臣/太政大臣) which was Grand Chancellor/Prime Minister and he became the go-to consultant for political and religious matters. Dōkyō’s rose to power was an overnight jackpot and the obvious favoritism for him didn’t bode well in the political stage. This would eventually set the stage for the scandal which involves the shrine.

Usa Jingū Encountered Its First Scandal in History

So how did the shrine got involved in this scandal? One day, the local priest interpreted an oracle which claimed the realm will be in peace if Dōkyō becomes the Emperor. Oracles were used by priests to interpret messages from the gods and predict future events. However, they were also subjective to the individual’s interpretation and the messages were usually ambiguous.

The court officials were shocked as only imperial descendants are eligible for the throne; even till this day. Unable to comprehend the situation, the Court decided to send an official named Wake Kiyomaro (和気清麻呂) to confirm the findings. When this happened, the priest immediately reissued another proclamation which stated only those from the imperial line and direct descendants of the Sun Goddess are eligible for the throne.

Note that the Sun Goddess refers to the Shinto God, Amaterasu (天照) and Japanese believed that the imperial line originated from her. This was a 360-degree turn compared to the previous oracle; most likely the priest realised that it was bad idea to go against the big-time politicians in the Court. Dōkyō (道鏡) was extremely pissed off at Wake Kiyomaro (和気清麻呂) and intended to execute him; but last minute intervention by his supporters saved his neck.

Before anything escalated however, Empress Kōken passed away and the Court immediately strip off the monk’s ranks and authority and exiled him. The Court also sacked the priest who issued the proclaimation, on grounds of deceit.

The Aftermath of the Scandal

While this incident remained relatively unknown; had Dōkyō’s accession came to fruition, Japan would end up being a theocratic country and ruled by Buddhism. Can you imagine a Japan with no drinking bars, karaoke outlets (カラオケ) and delicious barbeque skewered meats; that would be unthinkable!!

Regardless of the amount of contribution to promote Buddhism by Empress Kōken; most historians remembered her scandalous relationship with the monk. The incident left behind a tainted image of having a female ruler in the Court and there would not be another female ruler until the 1600s. The Court had enough of Buddhism meddling into their affairs and decided to move the capital once again in AD 794.

Despite remaining a major shrine, Usa lost the favour of the Imperial Court to other newly established shrines. The shrine would remain a quiet life for the next few centuries like a retiree throughout the aristocratic and artistic Heian period (平安時代). Unfortunately, that not be the end of the shrine’s misfortune as it will be embroiled into major civil wars and awkward positions in the later periods.

Next in History: Usa Jingū Enters the Age of the Warriors

An Intro to the Genpei War

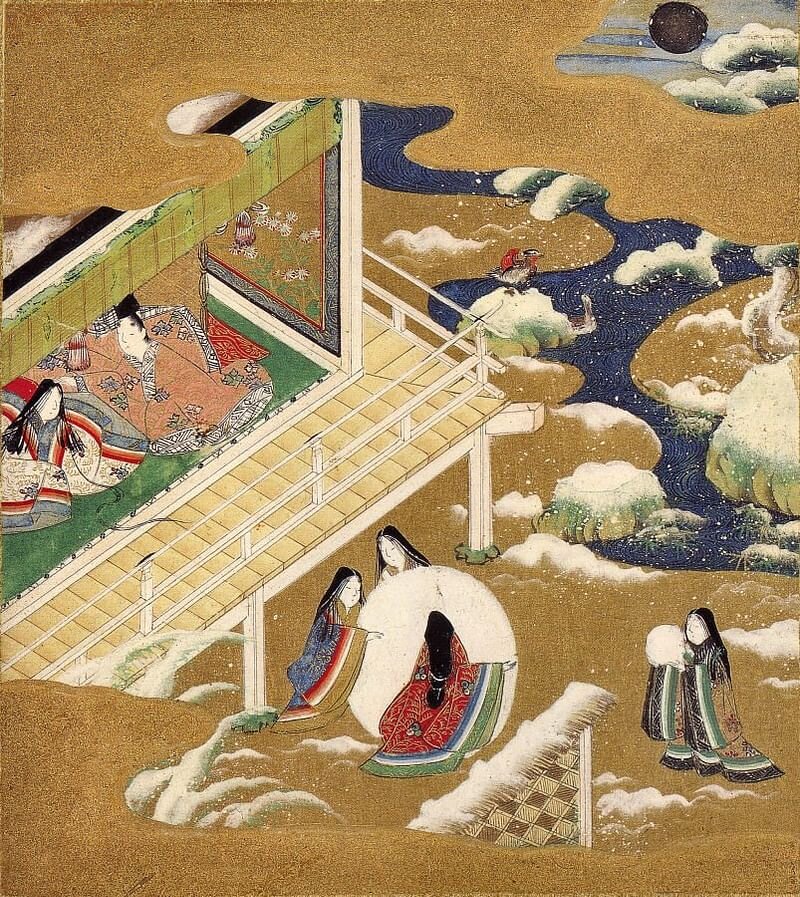

Good times were transient; as the aesthetic-centric Heian period (lasted from AD 794 until the 1180s) transitioned to the eventual crude Kamakura period (鎌倉時代). Prior to this, the shrine was remained untouched given that temples and shrines were important in an artistic and religious society.

The eventual decline of aristocracy rule had been a long process throughout the period; mainly contributed by the rapid expansion of the Imperial family. Emperors gave birth to dozens of children; forcing the Court to demote them as nobles and bestowing them new family names. This caused the birth of various clans that competed amongst each other within the Imperial Court for power and prestige. Among the two most well-known were the Taira (平); masters of the sea and naval warfare and the Minamoto (源); whom was mentioned earlier in this article.

This event is known as the famous Genpei War (源平合戦). For the Japanese language fans, the name Genpei is a combination of the Chinese/kanji characters (漢字) for both Minamoto and Taira (源 + 平); using the Chinese pronunciation called onyomi (音読み).

The Rise of the Taira

At first, it was the Taira defeated the Minamoto in AD 1159 in a power struggle incident known as the Heiji Disturbance (平治の乱). The leader of the Taira clan, Taira no Kiyomori (平清盛) executed the leader of the Minamoto and exiled his sons; apparently he thought that sparing the son was a good idea for his PR. Turns out this would bite him later on.

Kiyomori ruled the Court as Daijō-daijin (太政大臣) which was Grand Chancellor/Prime Minister at that time. While he was both a skilled warrior and a politician; his personal motto was ‘my way or the highway’. He wasn’t tolerant and discriminatory to those who opposed his policies, which alienated him further from his allies that once supported him. Consequently, he earned a reputation as a tyrant to this day, especially in the history textbooks.

The Revenge of the Minamoto

Needless to say, Kiyomori’s antics did not fare well with the Imperial Court and the other samurais in the land. The son of the Minamoto leader who was banished, Minamoto no Yoritomo (源頼朝) saw great opportunity for vengeance. He rallied various other disgruntled samurai (侍) clans, formed a power base in the Kanto region (関東地方) and went on a military campaign against the Taira; like an episode from Game of Thrones.

Unfortunately, Kiyomori passed away of illness in 1181; possible of fever and this affected the overall leadership of the Taira. Legends said however that Kiyomori’s fever was so hot, that it would burn anyone who came close to him; possibly a karmic retribution as a dictator.

The Minamoto wasted no time and rode on this momentum and defeated their nemesis in a series of battle. Subsequently, the Taira withdrew from the capital and retreat to Western Japan. Eventually, the clouds of war would soon loom over the sacred shrine.

Epilogue

In part 1, we see the inception of the shrine and how it had survived throughout the age of development for religion and arts in Japan. What would be the fate of this beloved shrine as it enters the period of samurai warriors? Find out more in The History of Usa Jingū (Part 2 – Towards the Modern Age). Or if you excited in exploring the shrine complex itself, check out my previous post Usa Jingū – A Complete Travel Guide to Japan’s First Hybrid Shrine for more details.